Construction: Cycles and Considerations in Lending

By Michael Beaver

The construction industry has an idiosyncratic cycle for financial standards unlike any other. This article will help demystify lending in the heavily segmented construction sector, a very cyclical industry that mirrors our economy. And while we don’t see a lot of shopping malls being built these days, hospitals and oil and gas pipelines go through periods of significant infrastructure expansion and growth when those sectors are hot. Most construction companies typically specialize in building in one sector or another before, so when considering lending to a construction firm, it’s important to understand if a particular industry segment warrants investment based on economic trends in the marketplace. Lenders must be aware of the potential up or downside of a particular segment of the economy at any given time.

Construction industry financial reporting and accounting are unique. In fact, financial statements in the construction industry are based on estimates – a fact that in and of itself makes most lenders’ heads spin. Additionally, accounts receivable, payable and labor all operate a bit differently in the construction sector. Take labor for instance, where a skilled labor shortage has construction companies scrambling to keep crews on jobs. Companies pay workers on a weekly basis as they attempt to retain the carpenters, electricians, plumbers and others assigned to a particular project. Accounts payable and receivable work on cycles that do not match what investors are normally accustomed to seeing. It’s possible a construction company could receive payment at the beginning, middle and end of a project. Yet, they have to pay building material suppliers on a monthly basis and skilled laborers weekly. As such, it is important for lenders to know how disciplined a borrower is with their projects and financing. Are they using money from project X to pay for supplies or labor for project Y?

Other common pitfalls lenders need to be aware of include recognizing contractors who do not manage their projects and money well and those that lack an understanding of their working capital needs. These deficiencies often manifest themselves in lack of cash management and controls. Poor budgeting and implementation can lead to cost overruns, excessive overhead and problem projects affecting the entire business (i.e., claims, liens, litigation). Insufficient financials can damage bank and surety relationships. It’s important to be mindful that standard operating procedures (SOP) are in place, including:

- Technology/platform (ERP, Best in Class, Office templates/shared drive, Manual or combination of the above)

- Resources needed to develop SOPs, safety programs and training programs

- Sufficient estimating and take-off processes

- Reliance on leading indicators versus lagging indicators

- Execution capabilities and span of control issues

Signs of trouble can show themselves in a number of ways. Is there working capital growth on the balance sheet? Has the company taken on expansion plans into new industries, geographies, or service offerings? Are there delays in receiving monthly financial information? Has there been a change from auto payment to payment by check? Have disbursements for accounts payable slowed or ceased to function? Is leverage rather than equity being utilized to finance the company?

Historical due diligence is not the only important diligence when weighing loan agreement contingencies. Lenders must also closely follow the work in progress report (“WIP”). The balance sheet and the work schedule by project can offer insight to the company’s financial strengths and weaknesses. Be aware, as a lender, if you’re not thoroughly knowledgeable about the construction sector financial practices, you can be caught off guard with investment dollars not being used for their intended purpose. A common scenario for construction companies is possessing a $50 million of revenue backlog with a need for $70 million in cash to finish the project as the revenue backlog was overbilled. Additionally, a common construction sector practice is to bill for work that hasn’t yet been performed. And, it’s not unusual for money paid on one project to be used for another project.

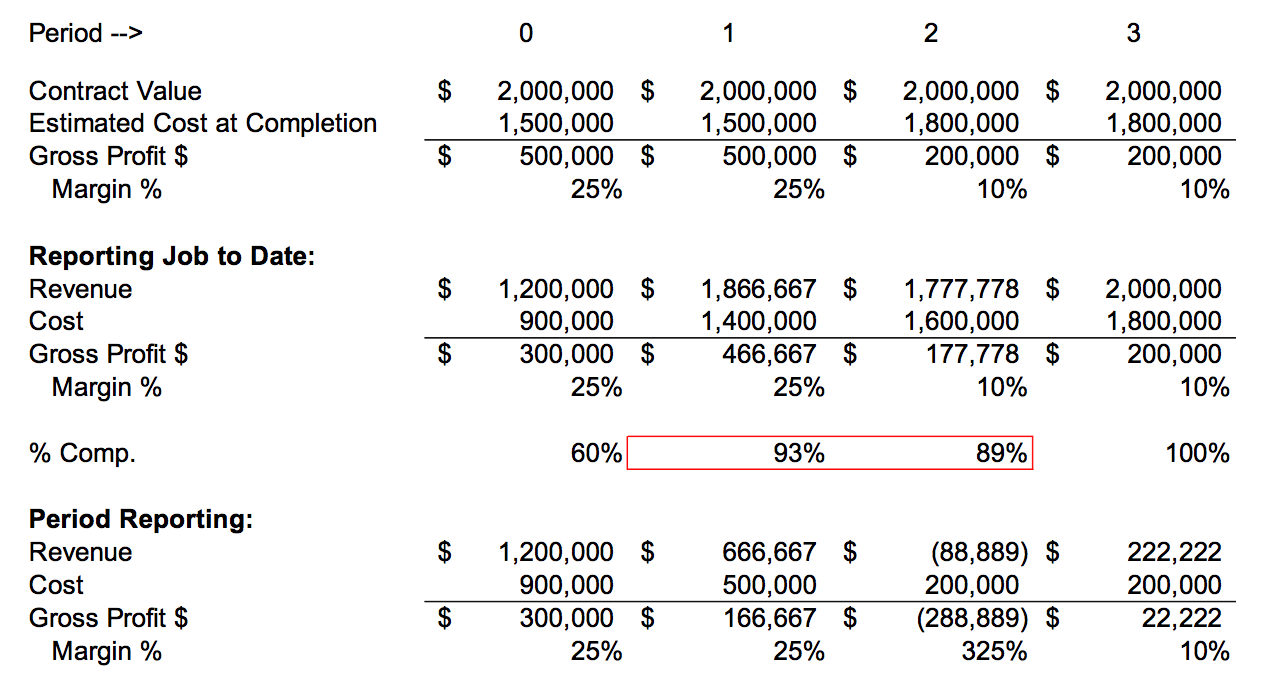

Percentage completion accounting (“POC”) makes a contractor’s financial statements an estimate. How real is the revenue number? Below is a sample on how POC accounting can create a period with negative revenue.

Evaluating a company’s credit stance, net income, EBITDA and cash flow provides an essential view into a construction company’s financial well-being. Understanding their balance sheet, leverage, working capital and asset value (book vs. appraisal) provides a deeper dive into daily operations. And, while the numbers typically tell most of the financial story, it is also important to understand the company’s ownership structure. Is this an owner-operated business or is it run by a private equity firm? Personal relationships between lenders and clients can have an effect on how loans are managed, especially when performance goes awry and difficult decisions have to be made.

When seeking to understand the financials of the business it is also imperative to know the trading multiples, projected base and leverage positions. Trading multiples should be low. Project-based contractors at 4.0x and service-based as high as 7.0x. Leverage should be at 2x to 3x.

Securing Your Loan

Is the senior lender really senior? That’s a loaded question if ever there was one, considering there are subcontractors with mechanic lien rights working on multiple projects simultaneously. Further complicating matters is the nature of accounts receivable collateral for a construction project when a surety bond has been provided for the project.

Surety bonds are required for most municipal and government construction projects, but lenders don’t necessarily appreciate a project that has them in place. Surety bonds and subcontractors could put the lender into third position when looking at account receivable collateral. If a subcontractor’s work has been completed on a project and they haven’t been paid within 90-120 days (depending on the state where the work took place), a mechanics lien can be placed on the property. If the contractor fails to live up to their financial agreements and a surety bond is in place, it will be enacted to pay money due to subs. This also means the surety company will claim the accounts receivables for the bonded project. This leaves the lender three rungs down in the payment pecking order when looking at accounts receivable collateral. When a contractor fails to pay their subs and there is no bond in place, the project owner may very well step in to avoid having any liens placed on their property and, write joint-checks with their contractor to pay off the subcontractors. When a surety bond is in place for the project, the surety insures the subs are paid and the project is performed; providing a level of security for the property owner.

Deciding to lend comesdown to the strength and credit worthiness of the contractor. There’s no divining rod to lending into the construction sector. Some lenders are willing to take on risk at higher interest rates with an eye on a company’s collateral, but counting on collaterals is akin to throwing the dice at a craps table. Collateral does provide a degree of security in case money dries up, but recouping a loan through collateral is far from foolproof. When it comes to physical assets, asset-based lenders are extremely reticent to attaching value to equipment unless it is easily locatable and not used for specialty applications. A remedy for a lender in a project-based scenario, when the contractor defaults leaving uncompleted projects, is relying on equipment owned; there are important nuances lenders need to be aware of when using equipment as a collectible asset. One has to consider: Is it industry-specific or general construction equipment? By way of an example, energy company contractors use specialty equipment to build pipelines. When the energy market tanked, the associated equipment/collateral lost value. It’s extremely important to know the exact equipment being used for collateral. First question should be: Is it specialized equipment or general construction equipment (i.e., a side boom vs. an excavator)? Another concern is whether the equipment is readily available. And, you’ll want to know its resale value in case you need to liquidate the holdings.

Lending into the construction sector can prove to be a lucrative decision if extensive due diligence is conducted deep into a company’s financials. There are a wide range of factors and potential pitfalls to consider, understand and navigate properly. You’ve heard the phrase, “If I owe the bank that’s my problem. If I owe the bank a substantial amount of money, it’s the bank’s problem.” Success and profits can be had with a well-thought-out methodology, but an understanding of the construction-sector market factors is critical for success. TSL