- Equipment Leasing and Finance Association’s Survey of Economic Activity: Monthly Leasing and Finance Index

- Potential Impacts of Blockchain on Commercial Lending

- Construction Factoring – Building the Right Foundation Despite the Unique Challenges

- International Trade Finance in the New Era: Small Business Survival in a Big-Business Economy

- Lighten the Load: How Selling Charge-offs Can Jumpstart the Turnaround Process

Public Sector Debt Explosion & Anemic Job Growth: Will the Reckoning Come Later this Decade?

November 18, 2013

By Marc D. Wagman

Though the United States remains the global leader in technological innovation, the world’s biggest economy is stuck in a low-growth quagmire out of which it cannot seem to emerge. There is a begrudging sense of a “new normal”, an unprecedented acceptance of low expectations that high single digit GDP growth is no longer possible in America. The size of government grows larger in the U.S. economy with each passing year as large underfunded entitlement and pension programs must be financed with borrowed money. Fortunately for borrowers now, this is occurring in an artificially very low interest rate environment thanks to a Federal Reserve Bank balance sheet which is several times larger than it was five years ago prior to the financial crisis.

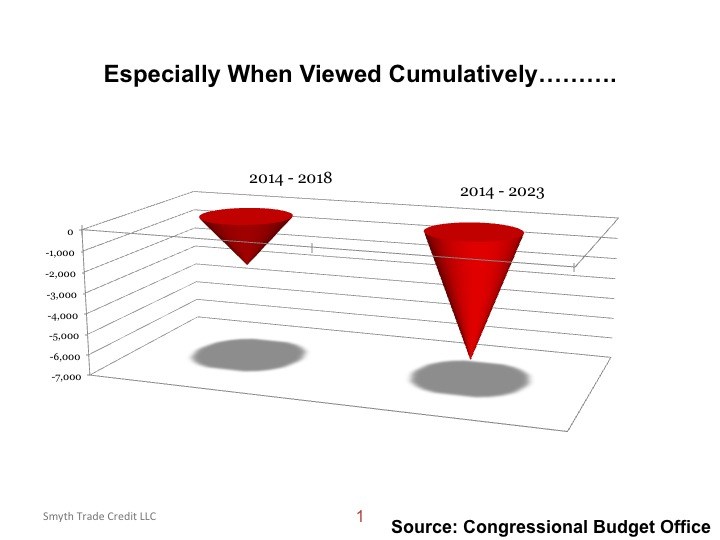

Political gridlock in Washington is all the American people have come to know over the past decade. Massive public sector budget deficits still loom large at federal, state and local levels, often funded by high levels of borrowing. At a federal level alone, projected cumulative deficits have the potential to crowd out private sector borrowers later this decade especially in a high-interest rate environment. Based upon figures provided by the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office as of October 2013, the following graph (expressed in thousands of $billions) illustrates the staggering amount of money the U.S. Government will have to borrow in the coming decade to fund its projected revenue shortfalls.

To be clear: higher borrowing costs are coming, it’s not a question of if, but when. Congress and the White House have recently needed to battle each other more often on the size of the U.S. Treasury’s maximum legal borrowing authority. What if one day the Chinese or Japanese central banks get sick of waiting for resolution from Washington on this issue and decide to no longer lend money to the United States Government for such poor rates of return?

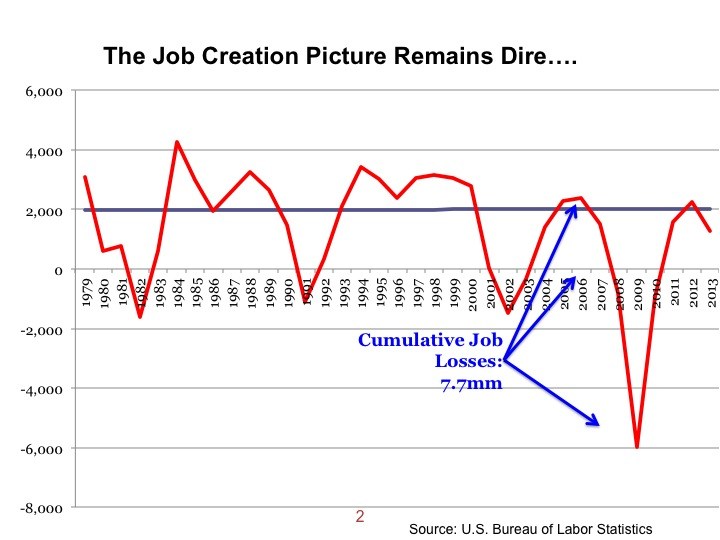

One supposes that if there was significant levels of private sector job growth to lead the economy out of its doldrums and create enough incremental tax revenue to fund this unbridled governmental growth, perhaps there wouldn’t be so much fear from the capital markets’ perspective. The reality is that, per the following illustration, private sector job growth has never been so historically poor coming of any post-war downturn, especially one as severe as the recent Great Recession. Between the years of 2008 through 2010, the U.S. lost a staggering 7.7million private sector jobs.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

Three years later, America has recouped only about 5.1million of those lost positions. At the current monthly pace, it will take another 2+ years to return to where private sector labor force was pre-recession.

What is going to be the impact of all of these variables on the U.S. and global economies later this decade? What will happen to the value of the U.S. dollar and the ability of corporations globally to borrow money?