Troubled Farms Navigate Options

August 12, 2019

By David Johnson

The U.S. farm sector is a major industry. In 2017 the two million farms in the United States produced approximately $389 billion in agricultural products, a value nearly double that of 2002. Five commodities accounted for two-thirds of total production value in 2017, and the top ten states represented 54 percent of 2017 production value. Despite these impressive numbers, industry gains are not necessarily indicative of the gains for individual farmers: in 2017, 69 percent of production came from only four percent of farms (those with revenues > $1 million).[1]

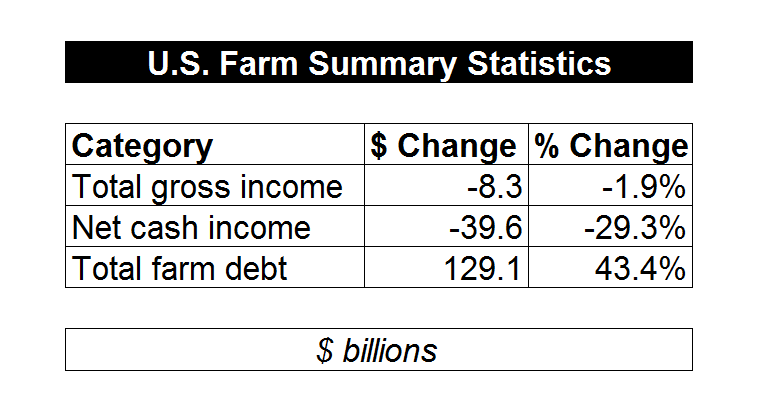

Today, the U.S. farm sector is in crisis and, by many accounts, the full scale and scope of that crisis is something this nation has not seen since the Farm Crisis of the 1980s, when a confluence of micro and macroeconomic factors led to the failure of thousands of farms. Today, the challenges are both varied and formidable. Macro challenges include historic flooding in the Midwest, plummeting demand from China due to trade tensions and an outbreak of swine flu, and significant concentrations in a small number of agricultural commodities (the top five accounted for $255 billion in production value in 2017). The micro challenges today are familiar, and worrisome, to lenders across specialties: flatlining revenue, climbing expenses, decreasing cash flow, and exploding debt levels (see Exhibit A).

Exhibit A: U.S. Farm Performance (Summary)

[1] https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/Highlights/2019/2017Census_Farm_Economics.pdf

USDA, NASS, 2017 Census of Agriculture

Source: “U.S. farm sector financial indicators, 2012 - 2019F”, USDA, Economic Research Service

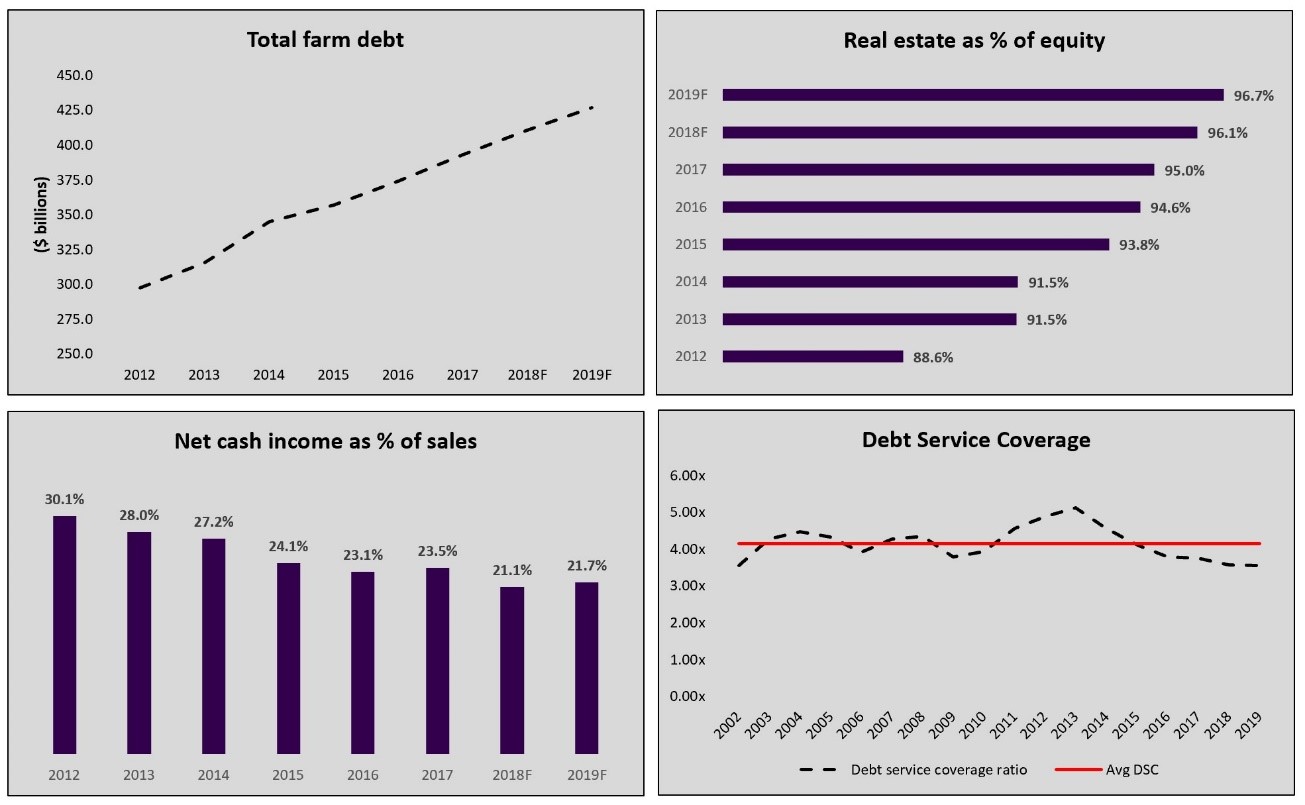

In many ways the challenges of the U.S. farm sector are a symptom of the overconfidence that is a natural by-product of success. Concentration in a limited number of commodities has led to the economies of scale one might anticipate. The implementation of new technologies and new equipment has given the leading farm operations a productivity advantage. The downside of this is that the very crop concentration that led to economies of scale has proven itself to be a serious weakness, as commodity prices (for corn and soybeans in particular), languish far below the highs of recent years. With farm cash flow trending down, more highly leveraged farm operations are finding their ability to service debt (up over 43% since 2012) to be severely compromised.

Signs of Distress

An analysis of recent financial performance in the U.S. farm sector is sobering. Total farm debt, at almost $430 billion, is up sharply in recent years. Real estate, arguably the most illiquid of monetizable assets on a farm’s balance sheet, accounts for nearly 100% of farm equity. Net cash income margin has fallen sharply. Debt service coverage ratio is at the lowest level since 2002. The boom that U.S. farmers enjoyed appears to be over (see Exhibit B).

Exhibit B: U.S. Farm Sector Financial Performance

Source: USDA, Economic Research Service

During the boom, the advantages of scale incentivized farmers to expand. Unfortunately, the capital structure of farms has not kept pace with innovations in production. As of 2017, over 80% of total farm debt was held by the Farm Credit System and Commercial Banks. Both groups are undoubtedly wonderful partners to have, but, in a potential workout scenario, these lenders have a limited set of options, and those can often seem draconian to struggling operators. As farmers navigate the current downturn, it will be necessary to expand their normal universe of capital providers.

Understanding Bankruptcy

No business owner enjoys the thought of bankruptcy. For entrepreneurs who have built their business or are proudly carrying on a family tradition, the very idea is distasteful. And yet, sometimes the simple arithmetic of a scenario is so uncompromising that no other avenue is available.

Despite the strong feelings that any mention of bankruptcy elicits from business owners, there is generally a great deal of misinformation regarding what it is and how the basic mechanics work.

There are three applicable chapters of the Bankruptcy Code for farm operators:

- Chapter 11: This is the most widely known. The goal of a chapter 11 bankruptcy filing is to reorganize a company. The company is granted an automatic stay, which halts creditor actions, while a plan to address creditor claims is created and submitted to the court. Bankruptcy is a highly legal process and involves a level of transparency that makes many small business owners uncomfortable, but it provides the strongest legal protection to preserve operations while restructuring liabilities (provided that the organization in question is viable).

- Chapter 12: A chapter of the Bankruptcy Code specifically devoted to the reorganization of small farms (debt of less than $4,153,150) and commercial fishing operations (debt of less than $1,924,550), this chapter provides a more customized solution to reorganizing a small operation and has been an area of heightened focus as trouble in the farm sector increases.

- Chapter 7: The chapter of the Bankruptcy Code that addresses the liquidation of a debtor’s property and the orderly distribution of proceeds to creditors.

New Partners for a Second Chance

In seeking to restructure their straining balance sheets, struggling farms are butting up against the limitations of their traditional capital structure: debt comprising real estate loans and operating loans (primarily made through the Farm Credit System and Commercial Banks), and equity that is largely tied up in the value of the land. During the decade-plus expansionary period that the U.S. farm sector enjoyed, many farmers came to see their traditional lenders and the loan structures they offered as sufficient to meet their needs. And who could blame them? Farmers are neither the first nor the last class of borrowers eager to work with amiable lenders offering loans with low interest rates and minimal reporting requirements. The challenge now is that the entire farm lending ecosystem is woefully lacking in true risk capital, and as the level of distress in the farm sector rises, a vicious game of musical chairs may be taking place, with only the lucky few farms emerging with a capital provider aligned with their current risk profile.

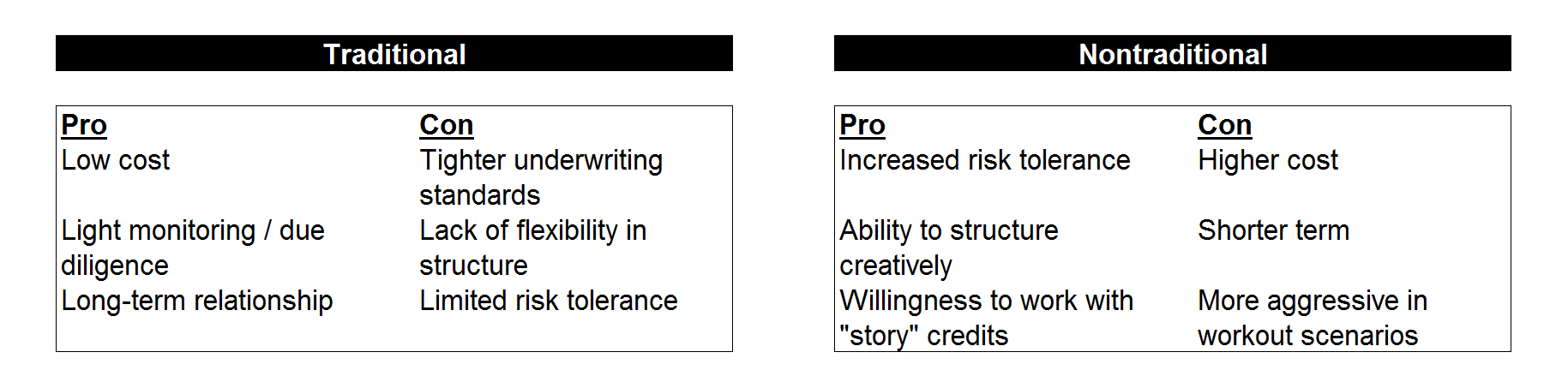

For those struggling farms that have a viable path to a turnaround, nontraditional lenders represent attractive partners (see Exhibit C). However, understanding the perspectives of each party will be crucial to ensuring that these new lending relationships realize their full potential. The simple reality is that farmers, even those who have enjoyed considerable success, tend to relish farming and loathe finance. This is where a solid advisory team can add value: creating a plan that is robust and defensible, negotiating with incumbent lenders and suppliers, attracting new capital providers, and ensuring execution of the turnaround plan that underlies the financing.

Exhibit C: Lender Type Comparison

Recent Engagement

The recent financial advisory engagement a of Chicago-based turnaround and restructuring firm illustrates many of the points highlighted in this article.

The client, a third-generation family-owned farm, was mired in a chapter 11 bankruptcy that had lost all momentum. Critical vendors had not been paid, communication between all parties was sporadic and of low quality, the primary secured lender had petitioned the court to have the case dismissed and converted to a chapter 7 (i.e. liquidation) due to lack of forward progress, and the farm owners were struggling with the sense that the situation was beyond anyone’s ability to fix.

Within six months of retaining a new financial advisor with a focus on restructuring and turnaround, the situation had taken a stark turn:

- Critical vendors were contacted and paid to ensure the ability of the farm to maintain operations

- A robust turnaround plan was developed, leveraging the operating expertise of the farm’s owners and the performance improvement and financial expertise of their advisors to optimize profitability, cash flow, and capital structure.

- Refinancing options were identified, with the first term sheet coming less than 90 days from the date of hire

In the end, a consensual Plan of Reorganization was filed, featuring a structure that included new money from a nonbank lender and a 20% reduction in principal for the secured lender.

Conclusion

Farmers are, as a group, honest, direct, and a bit insular. Many come by their dislike of finance honestly. But farmers are also highly practical; they understand that the current situation is dire and those that need to are willing to partner with principled actors who can guide them through the present crisis. Given the current depth and breadth of challenges facing the U.S. farm sector, it is that very practical mindset that will give farmers, and their farms, a second chance.

.png?sfvrsn=fcd0a496_0)