- ABL Navigates New Economic Crosswinds

- Gordon Brothers Appoints Liz Blue Head of North American Business Development, Retail & Real Estate Services

- Ares Commercial Finance Launches a Healthcare Asset Based Lending Platform

- Interview with SFNet’s Emerging Leaders Summit Keynote Speaker Dave Spandorfer, CEO & Co-Founder of Janji

- Kansas City Fed President Addresses Secured Finance Network Amid Market Turmoil; Vows to Fight Inflation

PART 1: Allou – A Firsthand Account of a Massive ABL Fraud

June 29, 2021

By Mark Fagnani

Allou Healthcare was one of the biggest frauds ever perpetrated against ABL lenders. What follows is a description of the case from an individual who was directly involved from day one. TSL will be publishing the entire article in two installments. In Part One, you will read how the fraud was perpetrated and how it was discovered. In the second installment, to be published in our September issue, you will read all the steps taken by the lenders and their team of professionals to recoup the loan and to punish the wrongdoers. This is a rare firsthand account of a significant fraud and you won’t want to miss it.

This story begins in 2001. By that time, I had been in asset-based lending for 25 years and had risen through the ranks of my company to be a senior leader and the person with oversight over all problem loans. While I would never say that I’ve seen it all, I had seen a lot. The same could be said for every member of our senior management team, many of whom had more than my 25 years in the industry. Despite that, this is a story about how a massive fraud was perpetrated against our company and our numerous co-lenders, right under our noses beginning with the day the loan was booked (and, as it turned out, many years before that). But it is also a story about our reaction to the circumstances and how we assembled a world-class team to uncover all the facts, recover as much of our loan as possible and ultimately send the perpetrators to jail. This is a story about lenders who, once the fraud was discovered, were tireless and aggressive and willing to spend substantial amounts on professionals in pursuing their remedies, which ultimately resulted in over $130 million in recoveries (better than 60%). This is also the story of how the agent and its co-lenders collaborated in developing and implementing a comprehensive strategy to gain control of the situation, manage recoveries from every available source and assist in the prosecution and conviction of the wrongdoers. The story began in 2001, but all court-related activities only recently ended, and the last convicted felon was released from jail in 2020. So, yes, it has gone on for a very long time and at great expense. The mistakes made by us in 2001 can easily occur today and the lessons learned are as relevant now as ever. My hope is that the reader will not only enjoy the story but learn from it.

Allou was one of the biggest ABL frauds ever documented and, to my knowledge, there has not been another one like it. It is a cautionary tale for all lenders.

In September 2001 my employer, then known as Congress Financial Corporation, (and subsequently to become Wachovia Capital Finance), closed on a $200MM loan facility for Allou Healthcare and its subsidiaries. Allou was a distributor of health and beauty aids and essentially sold everything you would have then expected to find in a drugstore, from shampoos and cosmetics to tissues and diapers. Through a subsidiary called Sobol, they also distributed prescription medicines. Winning the deal was somewhat of a coup for us as our head of marketing, Barry Kastner, had tracked the company for some time without success, but finally broke through and signed Allou to a multi-year credit agreement. We were thrilled. Up until this time, Allou had financed with other bank-owned ABL shops for at least the preceding 10 years. Our co-agent was Citicorp and we each held $50MM in the loan facility. In addition, there were several other co-lenders in the deal and some of them had actually sold participations to smaller lenders. In total, there were 10 lenders sharing in the facility. A few of the lenders in our group had been lenders in the previous loan facility as well. The deal was structured as a revolving facility with a blanket lien on all of Allou’s assets. We advanced 85% against A/R and 50% against the inventory. Allou was the 16th largest publicly traded company on Long Island and was listed on the NYSE. Annual audits had been prepared for years by a relatively small local CPA firm. At our insistence, the company engaged a large national firm for annual certified statements and, when that firm failed, another Big 8 firm was engaged as the lead partner went over to the new firm. Interim quarterly financials continued to be prepared by the small local firm. We also had personal guarantees from the three primary officers other than the CFO. The PGs were joint and several and limited to $10MM.

The company CFO was an individual we will call David S. He was a very polished, very charismatic individual, dressed in expensive suits and ties and was very articulate. It was David S. who met with the Wall Street analysts to discuss results and plans and it was with David S. that the agent had all interaction. He negotiated the entire loan agreement and signed the loan documents. He was the face of the company, but we were later to discover that David S. had little to do with the actual running of the company and primarily acted as a shield for the other officers who we later discovered had previous financial difficulties. This was mistake number one. We failed to familiarize ourselves with and meet all of the officers of the company. Today, in 2021 all regulated banks and most non-regulated lenders are required to perform KYC procedures and that is all well and good but is not a replacement for actually meeting and getting to know your clients. Harder in this COVID era, but still very relevant.

In the early days of our relationship, all seemed well. The company reported A/R and inventory on a weekly basis and interim financials reflected modest profits. A/R turnover trends were in line with those revealed in our initial survey field exam as were dilution trends. The company had hundreds of customers and thousands of small dollar invoices. WalMart was the largest customer, making invoice verifications difficult and inconclusive, as the results of any testing we did were small as a percentage of A/R. However, other than the fact that the company consistently used the full credit line and did not maintain significant liquidity, nothing appeared to be out of the ordinary and this was attributed to the company keeping A/P very current.

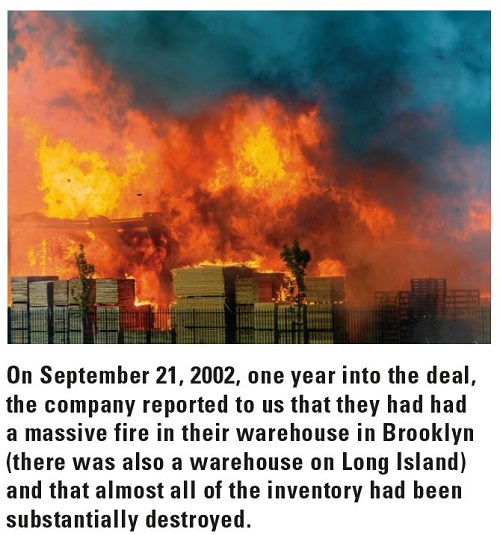

On September 21, 2002, one year into the deal, the company reported to us that they had had a massive fire in their warehouse in Brooklyn (there was also a warehouse on Long Island) and that almost all of the inventory had been substantially destroyed. This was obviously distressing news; however, the company informed us that the inventory had been fully insured so, despite the fact that inventory with a cost of $100MM had been destroyed, insurance proceeds were expected that would more than make both the lenders and the company whole. We had a Lenders Loss Payee Endorsement in our favor and accordingly assumed we would receive a check in due course. Our advance against the inventory had been $50MM and we now had an overadvance in that amount, which would have to be repaid with the insurance proceeds. At this time, we believed the company had been the unfortunate victim of an accident and accordingly we planned to support them through this troubling period. A salvage expert was retained by the insurance companies to dispose of any inventory that survived the fire and that could be sold albeit in a soiled or damaged state. He was also responsible for removing all inventory/ rubble from the warehouse. During this effort, 15 to 20 40-foot dumpsters were filled with waste. This is important as it validated that there was merchandise in the warehouse at the time of the fire. This turned out to be very important based on future events. However, insurance personnel on site during this removal process were concerned that certain items or the remains of items that should have been present based on inventory reports were not found.

Shortly after the fire, the Fire Marshall issued a report stating that, in their opinion, the fire was of a suspicious nature and they suspected arson. This report, combined with the suspicions noted above, prompted the insurance carriers to withhold payment on the claim pending further investigation. Allou maintained that vandals must have broken in and started the fire.

At this juncture (mid-to-late October 2002) we still had no reason not to believe the company or to discontinue our support. We continued to finance on a daily basis based on new sales and new purchases of inventory. As the days turned into weeks and we received no payments on the insurance policies, the lenders obviously became concerned. The insurers began conducting EUOs (examinations under oath) of certain members of Allou management, causing further delays. The insurers also challenged our lender loss payee endorsement, an argument we eventually won but which caused even further delays and was not achieved without first having to litigate with the insurers. (A sign of things to come.) We pressed the company to come up with an alternative solution to clear the overadvance. David S. informed us that he was negotiating the sale of Sobol (the prescription drug distributor) to a well-known entity that we knew had the wherewithal to close a deal. He represented that the purchase price would be roughly $40MM and would substantially clear the overadvance and that, once the insurance proceeds were finally received, the company would clear the balance and have significant availability. We were relieved to hear this news and awaited further developments.

In March of 2003, Otterbourg, as counsel for the lenders, and Proskauer as counsel for the company, initiated a lawsuit against the six insurance companies in state court as following, their investigations, which were inconclusive, they continued to withhold payment. A word about the insurance carriers: While there was one policy, there were numerous carriers, with each having liability under the policy at a different dollar level so the first carrier was responsible for claims up to their limit, then the second carrier up to their limit, then the third, etc. The carriers involved were household names: Travelers, Seneca, Lloyds, Royal, Chubb, and Zurich.

Also in March we elected to conduct a field examination to insure that the remaining collateral was still performing and that reporting was accurate. In addition to examiners at the borrower’s main location, we arranged a site visit to a satellite warehouse in Nyack, NY. We were not aware that the Nyack location existed until our examiners at the company’s HQ discovered the existence of this location on the inventory perpetual. The company’s failure to inform us of this location was another red flag. Under the terms of our agreements, all borrowers were required to notify us in advance whenever they opened a new inventory location so that insurance could be updated, landlord waivers obtained and, in those days, UCCs filed covering the location (no longer required under the UCC). On the very first day of our visit to Nyack our examiners called to say that they had been denied access to the warehouse and that the warehouse personnel were being uncooperative. I will never forget this call. Our entire senior management was together in a conference room as we had convened credit committee. When the call came in, we had it transferred to the conference room. We all heard the news at the same time. You could have heard a pin drop for a few seconds and I believe the hair on the back of each person’s neck went up as lack of cooperation is always a red flag, and especially given the current situation. The examiners were instructed to let the warehouse manager know that they would be returning the next day accompanied by senior personnel and then to leave, but to return the next day to meet in the parking lot. The following day, we were once again denied access. I had a brief closed- door meeting with warehouse personnel, explained that we were in the midst of what we regarded as a possible criminal investigation and that, if our worst fears were confirmed, anyone assisting the company would be regarded as colluding with the wrongdoers. This was a complete bluff on my part, but seemed persuasive as we were ultimately allowed to enter the premises.

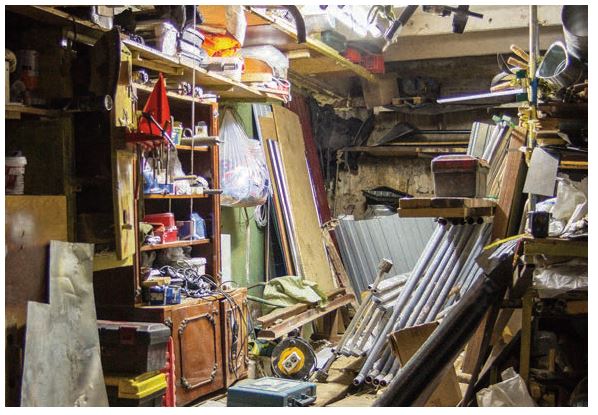

The inventory was in shambles. It appeared that what was there had just arrived and been unloaded without any order or system and was just piled in a heap. There were no aisles and there was no way we could perform test counts. Another conversation with warehouse personnel persuaded them to restack the inventory in some semblance of order so that we could return and do some testing. We returned a few days later and indeed the inventory was now organized such that it could be inspected. Almost immediately it became apparent that all was not well. For certain items, our counts went well and proved accurate, but the costing was completely out of line.

For example, while we accurately counted almost 130,000 room deodorizers that typically sell for about $1.99 each, we found that they were costed at $8/unit, an overstatement of roughly $1,000,000. We found cosmetic containers that should have had powder in them that were empty, yet valued as though they were full. We found items marked as “for export only.” We found old, outdated inventory and, when we tested the perfume, while the quantities were generally right, we discovered that we were counting the little gift items that are given away for free, not bottles of perfume. Just as bad, these were off brand perfumes that were no longer popular. I vividly recall counting thousands of samples of Baywatch, swearing under my breath the entire time. In a nutshell, it was a mess and our conclusion was that the inventory reported at this location was overstated by at least $16MM. After several hours, during which things went from bad to worse, we elected to stop, thanked the warehousemen for their efforts and left. I called the office from my car and spoke to our CEO and chief credit officer, who were obviously not pleased. I told them I was driving directly to company HQ to confront the CFO with our results and ask if there were any explanations for this seeming overstatement of our collateral.

Upon arriving at the company’s location, I was left to wait for over an hour before being greeted. I went and spoke with our examiners on site at this location. They were having similar cooperation problems and had been instructed not to walk in the warehouse without supervision. The company also insisted on receiving our test count selections in advance, yet another red flag. To our examiner Robert Morelli’s credit, he refused to provide selections in advance as he knew this would compromise our findings. He and I toured the warehouse together and it was pretty obvious to us both that inventory levels at the Sobol section (caged and segregated as these were pharmaceuticals) were drastically low. This called into question the legitimacy of the claims that this unit was being sold. I should note here that it came to my attention that previous examiners had indeed “cooperated” with company personnel by furnishing our count selections to the company in advance of the actual counting. We should not have done this, as a company with the intent to defraud a lender will insure that those items selected for the test miraculously appear. Since ABL lenders typically only count a small fraction of the inventory and then extrapolate the results over the total inventory, successful counts of the test sample usually result in an assumption by the lender that the entire inventory report is correct, a fact that Allou, having been financed for years, knew quite well. Finally, David S. came to get me. I was introduced to all the other officers of the company by David S., who promptly left the meeting. I presented our findings to the assembled management team, who first denied everything and said we must be mistaken and who finally asked that they be given a few days to look into it and come back to us with a full report. Their demeanor during the entire meeting was disturbing. They were arrogant, dismissive, talked among themselves without addressing me and downplayed my concerns. I was by now completely distrustful of anything management said. For those of you who know me, you can only imagine my temperament at this point. I believe it is safe to say that all antennas were up at Congress. I steadfastly believed we had been defrauded and for the first time worried in earnest about the fire marshall’s findings. Others shared my view, but we agreed to allow the company a chance to explain. Declaring a fraud is not something a lender should do lightly and, while we were all anxious now, we needed more information.

I returned to our offices and gave a full report. We determined that we would give the company a few days to explain our findings while our team in the field continued the exam. Several days later the management of Allou came to our offices for a meeting. They explained that at holidays, Valentine’s Day, Mother’s Day, Christmas, etc., they assembled gift baskets for some of their customers and that all the components we found that we thought were overpriced or valueless were used in assembling these baskets. We asked that they provide purchase orders and a sampling of invoices that would corroborate these claims. Call this “trust, but verify” if you will, but we were no longer taking their word for anything. The company asked for a few more days to provide the requested documents. In the meantime, our examiners continued to have difficulty gathering information or getting cooperation. People that they needed made themselves unavailable; requested reports or documents were slow in coming or not provided at all. This is never a good sign and we all knew it. I, for one, was now convinced that the company was lying through their teeth and just stalling us and had committed a massive fraud on the lenders. At this point, we determined that we needed a consultant as eyes and ears on the ground. We introduced Dick Sebastiao of RAS Management Advisors (RAS) to David S. and suggested (read insisted) that the two meet in person.

Dick had dinner with David S. to discuss RAS’s services and potential involvement. Dick then went to the company headquarters the following day with David S. to get the assignment started. He was joined by 2 of his RAS staff. David S. introduced Dick and his associates to the company staff in accounting, warehouse and sales management and other departments and said RAS was going to help the company deal with the banks. While standing in the doorway to the conference room, Dick noticed a young staff member from Allou going into the president’s office and coming out with a personal computer tower over his shoulder. He immediately asked the head of warehousing and sales if he could please get the computer back and he did so. Upon receipt of the tower, Dick turned it over to RAS staff members for safe keeping. RAS kept the computer in the trunks of their cars for several days until we had the authority to examine it, which occurred after certain other events described further in this article. They rotated who had the computer and brought it into their hotel rooms at night. Talk about not trusting anyone. Dick was on red alert.

During these discussions, Dick requested authority from David S. to shut the warehouse down for the weekend to perform a complete physical inventory. He also asked for permission to change all of the locks in the office and warehouse and David S. approved. The timing of the inventory count was perfect because it was the month and quarter end for SEC reporting purposes. Dick called the accounting firm partner, whom he knew from his days in accounting (at Anderson), and told him it would be in his best interest to send over at least three staff people to observe the counting and take test counts over the weekend. He agreed and provided assistance. The RAS staff was also increased for this testing. Collectively, almost 80% of the inventory was counted by RAS and the accounting firm teams and they actually retested around 50% of those counts. We were certain the counts recorded were accurate and had been correctly reconciled.

RAS controlled all of the paperwork to ensure no tampering and controlled the input into the mainframe computer of all inventory counts into a separate file and then compared their counts to the company’s inventory system. When completed on Tuesday morning, we noted an approximate $70 million shortfall as compared to the inventory reports submitted to the agent. By this time, the head of IT and the controller had stopped coming in, so Dick located and engaged an outside computer firm (SBI) to monitor the computer system until we could get authority to control the system. Little did we know that, while the head of IT and the controller were no longer present at the company, they had remote access to the company’s computers.

When Dick called me to tell me about the inventory shortfall, I think he could hear me gasping for breath. (I was on the treadmill at the time, but this was shock, not being out of breath.) I immediately asked Dick to take a look at accounts receivable. He went to the accounts receivable manager and asked to see his aging. That gentleman handed Dick a stack of greenbar paper that was only about a half inch thick and totaled just $29 million. Dick asked him where the other $100 million was and he got defensive and said this list was all he knew about. The total receivables reported to the banks was $129 million. Dick instructed his staff to look deeper into this inconsistency and asked us to supply him with the receivable aging that was last reported to us. That report was over six inches thick and, as indicated above, totaled $129 million. Over the next several days, RAS tore into that report and found some extraordinary disparities. When they found these discrepancies, they increased their staff to around nine people for about three weeks, then cut back to a core group of three to four people. I determined that, while we were pursuing answers, we would not skimp on professionals, no matter the cost. We needed answers and fast.

Walmart was listed on the bank aging as owing $14 million. RAS determined that they really owed just $1.4 million and that their total sales volume for the prior year was just $14 million. The IT department had written a program to create invoices of varying dollar amounts, some as much as $2.7 million as recorded in the company books, but transmitted to Walmart electronically as $.01. In doing so, the invoice appeared in the Walmart system as valid. The way invoices were verified by the field examiners was to locate the invoice number in the Walmart system and check it off. We presumed that the fact that the invoice number was in the portal meant it was legitimate. The RAS staff went a step further and went into the Walmart payment system where they show what is scheduled for payment. It was there that they saw the $.01 invoices, which added up to nothing on Walmart’s books, but which fraudulently totaled around $13 million on the Allou books. The company had fabricated support documents for each of these phony invoices. This is an important lesson. We were a big firm, we had over 500 clients, we did thousands of field exams. We were not amateurs. Yet, verifying invoices as being in the portal stopped one step short of truly verifying their legitimacy and authenticity. We had failed to take that extra step.

RAS then went into more of the details and found the remaining $87 million of fictitious billings to other fictitious customer names. When making calls to verify those accounts, we received totally nonresponsive answers such as “go ask the CEO what that is all about if you want to know, etc.” The IT department had recorded all of these sales as being made by Salesman #2. Sales made by Salesman #2 were not included in the sales report given to the sales management team so as to hide that volume and were not included in the aging that the accounts receivable manager used for making collection calls, but were all included in the reports given to Congress. During these investigations RAS also reviewed cash receipts in detail. They discovered that checks received from “ABC Company” were shown as paying WalMart or other customer invoices. As we all know, only WalMart pays for WalMart and using a WalMart account. These were simply phony receipts making a round trip to pay off phony invoices, thus making it appear as though there was significantly more sales activity than there really was and this also explained why turnover (or DSO) always looked consistent. The company would create phony invoices, borrow against them and use some of those proceeds to pay down phony A/R. And do it over and over again. Our failure to examine actual checks and remittance stubs was another shortcoming on our field exams. We examined cash receipts registers and bank statements but, as with the A/R portal, did not take the extra steps.

While some of RAS staff were reconciling the receivables, others were investigating how the inventory fraud was perpetrated. They determined, with the help of SBI, that there was a non-existent Warehouse #8. The only way to access Warehouse #8 was, when you went into the inventory system, you had five seconds to notice a flashing box and then insert an A in that box. That gave you access to the details in that warehouse, all of which appeared to be fictitious. The purchases that were entered into Warehouse #8 were supported by fictitious invoices generated by the senior management, together with fictitious purchase orders and receiving reports. Sales and inventory management personnel did not receive information that included Warehouse #8 because it would have caused confusion on what to buy to fill real customer needs.

The company was making payments to these non-existent vendors through the accounts payable system by way of manual checks. Those payments would be debited to a prepaid account in the general ledger until month end when the controller would request (by email) support for each payment and then make a general ledger adjustment to transfer the prepaid balance to inventory. It was now clear that the company was maintaining two sets of books: one with the actual business and one created just for the lenders to inflate the borrowing base. Because the company had been financed by ABL lenders for so many years, they had learned what our field exam protocol was and knew what documents they needed to create to satisfy our testing.

As an example of the magnitude of the testing and analysis being done, I submit this excerpt from an RAS report: RAS examined all disbursements in the six years prior to the BK filing that were greater than $15,000, totaling ~$2.275B in disbursements.

RAS’ initial focus was on 42 entities believed to be affiliated with management. RAS examined ~$687MM worth of disbursements and, using a developed set of evaluation criteria, found that 70% ($475MM) of the disbursements were false purchases of inventory. The majority of these false purchase disbursements were round-tripped from the affiliated entities back to Allou to support AR collections to support the fraud.

Another 5% ($26MM) of the total disbursements were related to otherwise suspicious general ledger accounts (Loans & Exchanges, Officer 1099 & Donations). Some of these disbursements were for false purchases of inventory but many others were sent to third parties with no round-tripping, with the funds often moving overseas.

In addition, RAS examined another ~550 transactions totaling $64MM with ~400 different parties (different from the initial 42 noted above) that were deemed suspicious according to our evaluation criteria. The vast majority of these transactions were all deemed to be fake transactions with little or no physical backup. The same suspect general ledger codes were used as above and a majority of these funds were also moved overseas. As the reader can see, this was fraud on a huge scale and it took a firm the caliber of RAS to sort it all out.

While all of this was going on, the senior management, together with a few of their accomplices, broke into the warehouse/offices over the weekend when the counts were being made and took troves of documents out with them. The head of security was approached at home to give them keys for the new lock and refused, so they went to the warehouse manager’s house and got them from him. We had the break-in on the security cameras/ tapes and presented them in court at a later date. More on that later.

On April 1, while the work described above was ongoing, the senior officers of the company met with senior management at Congress along with counsel. They offered to pay us $10,000,000 under their PGs in return for full releases. That request received a swift and resounding NO. I think at that point we all knew we had a huge problem; the question was, just how big.

On April 8, Dick met with two of the partners at the company’s law firm to tell them what we had found and the extent of the fraud so they could deal with the necessary SEC reporting. Allou’s counsel was shocked and couldn’t believe our reports of the total amount involved. Dick left them to discuss it internally with their internal SEC counsel. They subsequently met with the senior management and filed an 8-K with the SEC and all trading was stopped.

Shortly after this meeting, while Dick was in the Company’s conference room with his team late in the evening, he received a call from the CFO with a menacing message. Having learned of the Brooklyn fire and related allegations, it made Dick nervous enough that he actually called his wife and told her to keep the alarm on in the house at all times and don’t ask any questions until this situation resolved itself, which did not happen until April 14. We were dealing with bad people.

Part two of this article was published in The Secured Lender's September 2021 issue and can be found by clicking here.